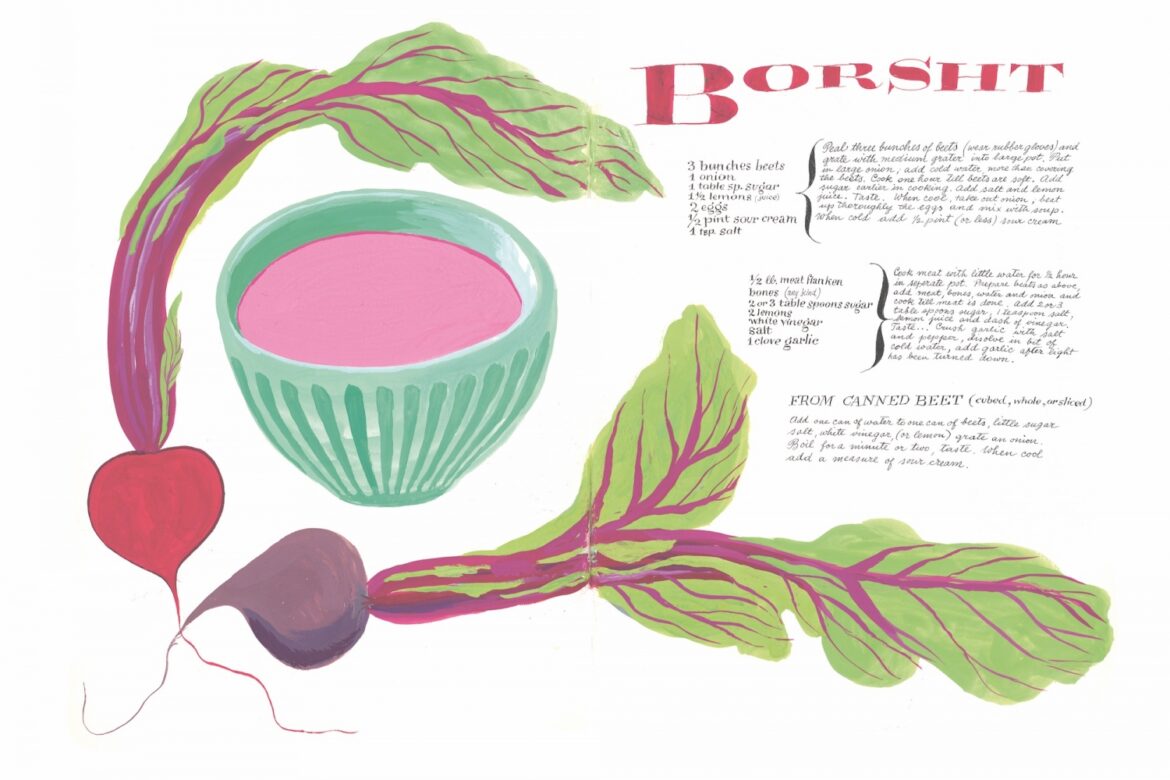

These days, most cookbooks are filled cover to cover with lush, spectacular, highly produced photographs intended to inspire the reader and present a goal for the home cook to achieve. However beautiful these photos are, they can also feel intimidating and unattainable–almost too perfect. Immaculately arranged and styled, these cookbook photos often feel more like they’re about lighting, digital pixels, and Photoshop than about making something with your hands in a home kitchen. Cooking is something you do with your eyes, your ears, your nose. You use all your senses to prepare a delicious dish. Given the personal, tactile nature of preparing food, you’d think a cookbook would visually convey how it looks, feels and tastes to make something–how it feels to you know, cook.

Illustrations can convey a love of food and aesthetic in a deeply personal, sensual, accessible way that other mediums just cannot. It’s what Cipe Pineles did in her cookbook in the 1940s. And its what many people are getting back to doing now. To some this might feel like the introduction of a new style. It’s not. Illustration and hand-lettering have been used in cookbooks as far back as the seventeenth century. It was terribly time consuming and expensive to create these pictures back then, so the black-and-white step-by-step instructions were a rare treat to find tucked in between the hand-set pages. As printing processes improved, so did cookbook illustrations. Simple black-and-white cross sections of how to carve meat, fish, and chicken became lush hand-colored etchings, then eventually four-color lithography. The first full-color cookbook was printed around the late eighteenth century, and the illustrations were as much about depicting a lifelike, beautiful dish as they were about showing the reader how to make it.

Then photography came along and replaced drawing as the way to represent reality. In case of the cookbooks, this meant finished dishes and table setting started to be demonstrated through photographs, and illustration as the primary language of cookbooks. Think of all those 1960s cookbooks with their pages packed with photos, by then illustration had been nearly pushed completely off the page. Then digital photography was introduced. Then the Internet. Enter food porn and websites filled with food photography. Then Instagram. You get where I’m going. And that pretty much takes us up to today.

Cipe’s Leave Me Alone With the Recipes and other illustrated cookbooks in its genre (yes, let’s state it-this is a genre!) takes us back to a time when there were no computers. There were no microwaves or fast food. There was no Photoshop. Instead, there was a long tradition of drawing and painting. There was attention, care and play. There was time and there was practice. And you could see that in every cookbook illustration–in Cipe’s and beyond. In our automated tech-filled, efficient lives, hand-drawn illustration gets us to think about process. To remember the things that only humans can create–in art, in design, and in the kitchen. Hand-drawn illustration in cookbooks brings us back to our most basic senses. And it does what Cipe’s cookbook does for me as an illustrator–it helps us remember from where we came.

Reprinted with permission from Leave Me Alone with the Recipes: The Life, Art, and Cookbook of Cipe Pineles edited by Sarah Rich and Wendy MacNaughton, with Maria Popova and Debbie Millman, copyright © 2017. Published by Bloomsbury.

This story was originally published in March of 2018.