The History and the Stars: Cider Making in the Hudson Valley

The Netherland settlers, who are lovers of fruit … have brought over and planted various kinds of apple and pear trees, which thrive well.

—ADRIAEN VAN DER DONCK, 1655

Mr. van der Donck, a lawyer in the Dutch colony of New Netherlands, wrote some of the Hudson Valley’s first cider history. He went on to describe successful farms, with unrivaled fruit so bountiful it was fed to pigs. A fierce advocate for the Valley, van der Donck blended hyperbole with documentation in an effort to attract more investment and immigration to the fledgling colony.

In today’s Hudson Valley, exaggeration is no longer necessary. Once something people “discovered,” cider has outgrown its adolescence and evolved into an integral part of the culinary and agricultural landscape, with ciders now being served in some of the world’s finest spirit boutiques and restaurants.

Apples, or Malus domestica, were introduced to North America by Europeans, although a few species of crabapples are native to North America and were cultivated by Indigenous peoples. Because apples do not grow true to seed, new apple trees would have sharp acids and bitter tannins, making them better suited for beverages than for food. In early colonial times, landed gentry, tenant farmers, and the enslaved all consumed cider made from prolific unnamed seedling apples that took hold in the cleared land of the new farms.

Most heritage apples were never named, but their descendants still thrive in the hills and margins. In 2008, Andy Brennan began harvesting the relics of these trees around his Wurtsboro home. Brennan brought the concept of seedling cider to the mainstream through Aaron Burr Cidery – named after the infamous founding father who fatally wounded Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Brennan and his wife, Polly Giragosian, only produce cider in years when uncultivated and seedling apples are plentiful. Uncultivated trees, when left to their own devices, typically bear substantial fruit every other year.

By the early 18th century, wild seedlings gave way to named and grafted apples that could be predicted to propagate. Most varieties, like Jonathan and Esopus Spitzenburg, were chosen for their prime eating and storage qualities, while in Newark, NJ, apples like Harrison and Graniwinkle were the basis of a relatively large cider industry. By the 19th century, settlers were propagating new and improved apple varieties, while horticultural societies were sponsoring European expeditions to find apples to improve the gene pool. The USDA collection at Cornell AgriTech in the Finger Lakes has 6,079 apple selections, some homegrown, others brought in from the Himalayas, the Caucasus, and the Tian Shan mountains in Central Asia—the birthplace of apples.

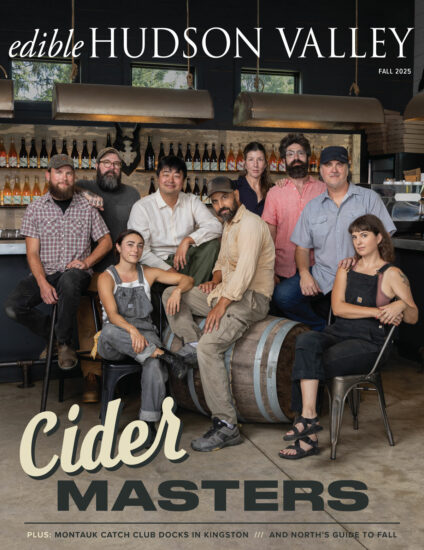

FEATURED IMAGE (TOP)

Cider Masters. Back row, L-R: Rose Hill Farm Orchard Manager Kevin Clark, Heartsby True Cider founder Denny Brownell, Richard Yi of Twin Star Orchards, Kimberly Kae and Matt DiFrancesco of Metal House Cider, Chris Jackson from Treasury Cider. Front row, L-R: Hannah Keggins and Fabio Chizzola at Westwind Orchard, Nika Carlson of Greenpoint Cidery.

The quest continues at Rose Hill Farm in Red Hook, NY. Founded in 1797, in recent years orchard manager Kevin Clark’s experiments have taken over. What was once just a block of Fujis destined for a now-shuttered wholesaler has become a “wonderland” of both cultivated and wild crab apples sourced from around the world.

What drives Clark? “Will the variety from Spain, or Southern California, or Quebec reproduce their same exciting qualities in the Hudson Valley, or will new characteristics emerge?” he says.

Rose Hill boasts 215 apples, 56 plums, 25 cherries, 25 peaches, five blueberries, three quinces, two apricots, and one medlar variety, with more going into the ground every year. The goal: Push the limits of experimentation and find interesting fruit combinations that yield truly unique ciders. Take the Golden Hornet, an ornamental crabapple the size of a dime. Alone it brings a mouthful of tannin and acid, but co-fermented with muscat grapes, we see what this Nebbiolo-like apple can do. Rose Hill’s ciders are about shedding expectations and orthodoxy to make something special.

of Metal House Cider

In the 19th century, apples in North America made a decided turn away from cider and toward fresh eating, assisted by new transportation possibilities and trade. In 1821, in Esopus, Robert Livingston Pell planted hundreds of acres of Newtown Pippins. Picked in late fall, these would slowly continue to ripen during their transatlantic journey on newfangled steamships, remaining delicious until spring. Those Pippins are no more, but Kim Kae and Matt DiFrancesco of Metal House Cider still cultivate trees on the Livingston property. A new planting of interesting varieties grows adjacent to long-neglected McIntoshes and Empires. Their ciders lean into wild pear, quince, and Cab Franc skins to yield an array of uniquely finished flavors. In one case, a two-year full-champagne method was used in conjunction with multiple fruits from Metal House, Twin Star, and the Montgomery Place Orchards at Bard College, where the climate-moderating effects of the Hudson help shield riverfront orchards from damage caused by spring frosts and other impacts of climate change.

Pell’s success opened North America’s fruit growing to distant markets. Commercial orchards became a viable business and a solid investment for the finance class and soon spread across the continent. Subsequent centuries of innovation in terms of variety, selections, storage, and transportation have all pushed apples to become more stable. In the modern era, apples are not only able to reach every corner of the globe, but they are available all year.

While cider declined in North America, it remained a fixture in places like Normandy in France, Somerset in the UK, and Asturias in the Basque region of northwest Spain. In the spring, cider houses or sagardotegi would open their doors and serve a feast of bacalao, omelets, and steak with copious amounts of cider. While French ciders boast complexity and natural bubbles, and the English are known for boldness, Basque ciders strike a special edge between fruity, acidic, funky, and refreshing.

A frequent visitor to the region during his wine career, Peter Yi was inspired to re-create that magic back home in New York. In 2015, Yi purchased Twin Star Orchards outside of New Paltz and began moving the conventional orchard towards holistic cider apples to supply the cidery Brooklyn Cider House. “People initially gravitate towards our fruit-forward ciders, but then become curious about our small-batch [varieties],” says Yi’s son Richard. “These ciders still embrace fruit flavor, but add complexity, tannin, acidity, and a bit of funk. Once they get a taste, the whole world of cider slowly opens up.”

By the end of the 20th century an apple’s shelf life became more important than flavor, an unfortunate consequence of apples becoming a global commodity. Declining apple prices left many orchards neglected, engulfed in poison ivy, and bittersweet as the apple trees are shaded out by pines and maples.

Heartsby True Cider founder Denny Brownell started taking note of these old and forgotten acres. He forages orchards that once provided substance and income fading into the landscape, re-employing these drive-by farms to craft single-variety ciders and co-ferments with cherries and berries.

Westwind’s Macouns and McIntoshes had been neglected for years when Fabio Chizzola purchased the property at Westwind Orchard. Here, Chizzola grafted older trees to heirloom and cider varieties, and planted several acres of new orchard. “I wanted to showcase the raw materials from the garden to the orchard,” Chizzola says. “We are a low-intervention in the cellar with no added sulfites and a focus on varieties for the apples to really shine.” Westwind is a world-class establishment that showcases what the Hudson Valley can do with its raw materials and a local breed of creativity and adventure.

at Westwind Orchards

The boundaries of cider are loose; drawing lines around categories can be a pedantic task, but much of the most exciting cider comes from these liminal spaces. Nika Carlson’s Greenpoint Cidery began in a Brooklyn bar and morphed into an exploration of local bounty just outside of Hudson. Vintage after vintage, she began experimenting: lilac for aromatics, wild grapes for acidity and texture, and black walnut for its deep richness. Carlson’s small-batch ferments are special because of the insight they give us into the creative possibilities of cider.

Making cider utilizing foraged apples is an act of conservation and sustainability. That mission is embodied in the origin story of Left Bank Ciders, located in downtown Catskill. Owners Tim Graham and Anna Rosencranz saw an opportunity in the discarded apples relegated to the compost bin of their local farmers’ market. Rather than see the fruit go to waste, they began pressing small-batch ciders from their home. They eventually connected with friend Dave Snyder, who was running a farm in Ossining, and in 2018, Left Bank was born. But while their dreams naturally gravitate towards planting their own orchard, the threesome stays closer to their roots. “We work towards simplicity and use regenerative practices, striving to leave things better than we found them, says Rosencranz.” Ultimately, existing orchards close to their cidery provide everything they need, and their creativity expresses itself through co-ferments with grape skins provided by award-winning winemakers like Stephen Casscles.

Left Bank Ciders

Seasoned growers know that experimentation is often hindered by environmental conditions that necessitate adaptability as a primary characteristic for tending a thriving orchard. In 1980, a hailstorm destroyed the wholesale prospect for Fishkill Farms’ entire crop. With the blemished crop unsuitable for grocery stores, they opened the gates to the community, who picked the apples themselves and yielded their most profitable harvest in years. Since then, the farm has reimagined U-Pick apples and caters to thousands of visitors each fall. In 2016, the farm launched Treasury Cider to further expand its offerings both on and off the orchard.

The Hudson Valley is past the point of having to persuade people to take a sip of an unfamiliar libation. With over 30 producers up and down the Valley, it has taken its place as one of the strongest cider-growing regions in the world. From the suburbs of Westchester to the rising Taconic and Catskills that flank the river valley, cideries that were once scrappy upstarts now have well-appointed tasting rooms and sophisticated food and dining experiences. As growers and producers mature, so do the consumers who have begun to dig deeper into the world of cider. Together we explore a richness of taste and a unique agricultural history that binds an old Hudson Valley to our modern senses.